What You Will Learn

You will learn how to create a basic Javalin application with filters, controllers, views, authentication, localization, error handling, and more. However, this is not really a full blown tutorial, it’s more a description of a basic structure, with certain points of the code highlighted. To get the full benefit of this tutorial, please clone the example on GitHub run it, and play around.

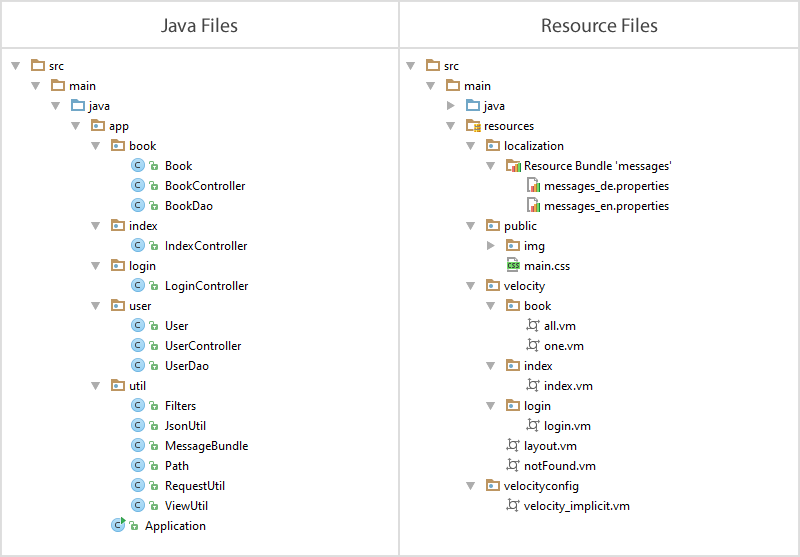

Package structure

As you can see, the app is packaged by feature and not by layer. If you need to be convinced that this is a good approach, please have a look at this talk by Robert C. Martin.

Application.java

This is the class that ties your app together. When you open this class, you should get an immediate understanding of how everything works:

public class Application {

// Declare dependencies

public static BookDao bookDao;

public static UserDao userDao;

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Instantiate your dependencies

bookDao = new BookDao();

userDao = new UserDao();

Javalin app = Javalin.create()

.enableStaticFiles("/public", Location.CLASSPATH)

.start(7000);

app.routes(() -> {

before(Filters.stripTrailingSlashes);

before(Filters.handleLocaleChange);

before(LoginController.ensureLoginBeforeViewingBooks);

get(Path.Web.INDEX, IndexController.serveIndexPage);

get(Path.Web.BOOKS, BookController.fetchAllBooks);

get(Path.Web.ONE_BOOK, BookController.fetchOneBook);

get(Path.Web.LOGIN, LoginController.serveLoginPage);

post(Path.Web.LOGIN, LoginController.handleLoginPost);

post(Path.Web.LOGOUT, LoginController.handleLogoutPost);

});

app.error(404, ViewUtil.notFound);

}

}

Before-handlers, endpoints and error mapping

If your application is small, declaring before-handlers, endpoints-handlers, and after-handlers all

in the same location greatly improves the readability of your code.

Just by looking at the class above, you can tell that there’s a filter that

strips trailing slashes from all endpoints (/books/ -> /books) and that any request

can handle a locale change. You also get an overview of all the endpoints, and that

there is an error-mapper for 404 errors.

Static dependencies?

This is probably not what you learned in Java class, but I believe statics are better than dependency injection when dealing with web applications / controllers. Injecting dependencies makes everything a lot more ceremonious, and as can be seen in this example you need about twice the amount of code for the same functionality. I think it complicates things without providing any real benefit, and before you say unit-testing: you’re not launching this thing into space, so you don’t need to test everything. If you want to test your controllers, then acceptance-tests are superior to mocking and unit-tests, as they test your application in the exact state it’ll be in when it’s deployed.

Path.Web and Controller.handler

It’s usually a good idea to keep your paths in some sort of constant.

In the code example above I have a Path class with a subclass Web

(it also has a subclass Template), which holds public final static Strings.

That’s just my preference, it’s up to you how you want to do this.

All my handlers are declared as static Handler fields, grouping together

functionality in the same classes (based on feature). Let’s have a look at the LoginController:

public static Handler serveLoginPage = ctx -> {

Map<String, Object> model = ViewUtil.baseModel(ctx);

model.put("loggedOut", removeSessionAttrLoggedOut(ctx));

model.put("loginRedirect", removeSessionAttrLoginRedirect(ctx));

ctx.render(Path.Template.LOGIN, model);

};

public static Handler handleLoginPost = ctx -> {

Map<String, Object> model = ViewUtil.baseModel(ctx);

if (!UserController.authenticate(getQueryUsername(ctx), getQueryPassword(ctx))) {

model.put("authenticationFailed", true);

ctx.render(Path.Template.LOGIN, model);

} else {

ctx.sessionAttribute("currentUser", getQueryUsername(ctx));

model.put("authenticationSucceeded", true);

model.put("currentUser", getQueryUsername(ctx));

if (getQueryLoginRedirect(req) != null) {

ctx.redirect(getQueryLoginRedirect(ctx));

}

ctx.render(Path.Template.LOGIN, model);

}

};

public static Handler handleLogoutPost = ctx -> {

ctx.sessionAttribute("currentUser", null);

ctx.sessionAttribute("loggedOut", "true");

ctx.redirect(Path.Web.LOGIN);

};

// The origin of the request (ctx.path()) is saved in the session so

// the user can be redirected back after login

public static Handler ensureLoginBeforeViewingBooks = ctx -> {

if (!ctx.path().startsWith("/books")) {

return;

}

if (ctx.sessionAttribute"currentUser") == null) {

ctx.sessionAttribute("loginRedirect", ctx.path());

ctx.redirect(Path.Web.LOGIN);

}

};

The above methods contain all the functionality that is related to login/logout.

The serveLoginPage handler inspects the request session and puts necessary variables

in the view model (did the user just log out? is there a uri to redirect the user to after login?),

then renders the page. The ensureLoginBeforeViewingBooks Handler is used in a before().

Localization

Localization in Java is pretty straightforward.

You create two properties files with different suffixes,

for example messages_en.properties (english) and

messages_de.properties (german), then you create a ResourceBundle:

ResourceBundle.getBundle("localization/messages", new Locale("en"));

The setup is a bit more elaborate if you clone the application (I created a small wrapper object with two methods), but the basics are very simple, and only uses native Java.

Rendering views

Javalin has native support on the Context object for rendering templates.

Let’s look at the login-page again:

public static Handler serveLoginPage = ctx -> {

Map<String, Object> model = ViewUtil.baseModel(req);

model.put("loggedOut", removeSessionAttrLoggedOut(req));

model.put("loginRedirect", removeSessionAttrLoginRedirect(req));

ctx.render(Path.Template.LOGIN, model);

};

The template needs access to the request to check the locale and the current users,

which we get from the ViewUtil.baseModel(req) method.

Example view

This code snippet shows the view for the fetchOneBook Handler, which displays one book:

#parse("/velocity/layout.vm")

#@mainLayout()

#if($book)

<h1>$book.getTitle()</h1>

<h2>$book.getAuthor()</h2>

<img src="$book.largeCover" alt="$book.title">

#else

<h1>$msg.get("BOOKS_BOOK_NOT_FOUND")</h1>

#end

#end

If the book is present, display it. Else, show a localized message saying the

book was not found by using the msg object that was put into the model earlier using ViewUtil.baseModel(req).

The view uses a layout template @#mainLayout() which is the page frame (styles, scripts, navigation, footer, etc.).

Conclusion

Hopefully you’ve learned a bit about Javalin, and also Java and webapps in general. Please clone the example and suggest improvements on GitHub.